Growing up

with France in the head.

LOVING FRANCE AND WRITING FRENCH LEAVE :

As

a child born during World War II and growing up in the years after I was very

much aware of the existence of France and Germany. As an early reader I read newspapers, in

imitation of my father Billy, whose chosen paper was the News Chronicle.

I found it easy to admire the brave French partisans who defended their country

from their powerful occupiers. In the years after the end of the war as well as

relishing of the victory, I read eagerly the tales of the liberation of France.

Even as quite small a child I felt lucky that Hitler didn’t get to walk down Whitehall

as he strode down the Champs-Élysées, swastikas flying.

My

sense of the existence of France and Germany took a richer and more informed

shape when I finally went to the grammar school at the age of 11. The so-called

Eleven Plus was a crude if effective generic IQ test across the whole

population which carried with it the reward of a well-resourced education.

So,

despite being the poorest of the poor, and living in a two-bedroomed house complete

with privy in a narrow street in a mining town in the North East, three of the four children in this family

passed the eleven plus for the grammar school. The fourth – my sweet brother

Tom, had been in hospital in the crucial year before and didn’t sit the test.

So,

at the age of eleven I entered the much revered grammar wearing the basic

uniform bought on tick from Doggart’s store. In this school the teachers wore caps

and gowns for assembly and the curriculum was geared towards white collar jobs

and the university.

I

knew I had entered a new world when – in the first week - I met Mr Phorson,

head of French, who addressed my class only in French from the moment we entered

the classroom. I was to discover later that this was called the Phorson Method.

Interestingly this Method was experienced in the next generation by my daughter

Debora at her school, at the hands of her teacher Mrs Snow (Madame la Neige!)

who had had been a student of Mr Phorson when she was at Durham University. By

then he was a respected professor in the French at the University. A footnote here

might be that Debora now lives in France

and writes lyrically about her life there. (See www.lickedspoon.com )

Through Mr Phorson’s meticulous teaching, by the

time I was 18 I was reading in French the works of Guy de Maupassant and

Honoré de Balzac

and the poetry of Verlaine and Rimbaud. But truly there is

balance in all things. A couple of years

after meeting Mr Phorson I also fell

into the hands of Mr Thompson, head of German, and eventually was reading Heinrich Heine

and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in German. At times I was bemused to

think that a country with such fine and sensitive literature as Germany could

fall into the trap of Nazi ideology

Anyway,

here was I in my shabby uniform, walking to and to the grammar from my Little

Street house, becoming a serious European while many around me expressed their

distaste for Germans: the boys playing fight games labelled German’s ‘n

English, or Japs ‘n English with pretend guns, the girls turning up their nose

when I practised quoting Goethe.

However

that feeling was mitigated for me as I absorbed the tenderness of Heinrich

Heine and shared the pain of a German soldier in as he froze on the Russian front in Heinrich Heine’s poem Der

Viele Viele Schnee.

And

then there was a salutary experience in the 1950s when my German teacher Mr

Thompson introduced the class to a visiting German teacher from Dresden who had

experienced the wipe-out bombing in that beautiful city by Allied forces towards

the end of the war.

Anyway,

this growing access to the language and literature of both France and Germany served

me, you might say, as an early lesson about the complex nature of my European

identity.

By

the time my third young adult novel French Leave was published, (still at

that time Hodder and Stoughton – not yet Headline…) in 1988 my son and daughter

were 22 and 24 respectively. You might say their childhood was my very long

practical study in the identity and world-view of both boys and girls.

So

it was a pleasure writing more closely in French Leave about a friendship

between two boys -Joe and his gypsy friend Skemmer as well as well as Joe’s

grandfather, who was part of their adventure. Never having had known either of

my grandfathers – or only having met

them in my imagination – it was great fun that as well as exploring the

relationship between Joe and Skemmer in that story I enjoyed inventing the

relationship between Joe and his grandfather who had experienced service in the

Second World War.

When

I wrote French Leave I had only been to France once when husband and I crossed the channel and wandered

around Normandy in our blue Jaguar* with our friends Bob and Lil. It was a deep

pleasure for me to hear French as she is spoken and observe the norms and

practices of everyday life we explored the small towns. There were so many

non-textbook lessons now to learn here – not least one about food.

One

outstanding memory was stopping in a small village in the mid-afternoon hoping

we could find some lunch. We stopped to get petrol in a garage and then walked

in to a workman’s café next door. The place smelled of food and spice and on its

long tables lay the detritus of finished

meal and empty wine bottles without their screw tops.

The

owner caught sight of us, ducked his head and said he was desolate that there

was no food left. At least I thought that was what he said. Then he shook his

head, open his arms wide and gestured for us to sit down at the end of the large

central table.

He

only took a minute to clear the table of the empty bottles and plates. ‘Madame!’

He called across to the e woman who was

stacking the dishes at a long open hatch.

In

no time glasses and full bottles of wine were placed before us and in twenty minutes

Madame was bustling across with a tray on each arm, loaded with a large

omelette. Delicious.

(* See also my poem Blue Jaguar on p44 in my collection With Such Caution)

Since

then I have enjoyed many such welcomes in many parts of France right down as

far as the Languedoc in the fae South West which, like my own north-east

England, has its own language which refuses to be put down.

For you! A taste of French Leave.

From Page 31

(Joe has been chasing around trying to get the paperwork right

for his grandfather to travel to France.)

Skemmer stood up. “And the woman said it might take ages to come, like?”

“Yes”

Skemmer glanced around the garage, which was deserted. Old Pollard

must’ve gone out for his dinner. Skemmer pulled Joe into to the little corner

office. On the cluttered desk was a white telephone smeared almost black with grease.

The phone number was stuck on the front with a brown cracking Sellotape. He rang

Directory Enquiries and got a number, which he proceeded to dial. When somebody

answered the phone he started to speak.

It dawned on Joe that Skemmer was

pretending to be him.

“… It’s my grandad, like. He was in the war. D-Day. You know… Whether

you’re in Ely shut his number… What… Dying like… Only a few weeks to go. He wants

the see the place where he… Yeah, yeah! Anything you could do to hurry it up…

Why thanks like. That’s really good.” Then he gave the details, the addresses

and all.

As Skemmer slammed down the phone Joe noticed how black his nails were.

right down to the cuticles: how black the oil was in the very pores of the

skin.

‘I don’t know whether he was she was just giving me the mouth, but she

says she’ll watch out for it. Give it some kind of priority. Said she wasn’t

allowed to but…”

Joe was mad that Skemmer knew exactly what to do. But he was curious as

well. How could somebody like Skemmer do all this?

…

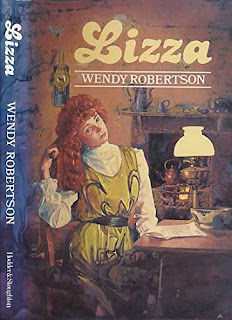

Cover

Copy of 1988 edition of French Leave

“17-year-old Joe shares a

close friendship with his grandfather, Bob, and when the old man suggests a

trip to France the scene of his wartime experiences, Joe eager to go to. They

travel in Bob’s old banger, gaily painted by Joe’s gypsy mate, Skemmer, who

accompanies them. There the confident and enterprising Skemmer is an odd

companion for Joe, whose shyness and lack of direction a stumbling block for

this, his first trip to the continent and his encounter with a friendly

outgoing American girl. A little rivalry, memories of truck tragic past and a

real present-day crisis also to help you learn more about himself, to establish

his first relationship with a girl, and come to terms with his uneasy family situation.

Publisher’s

Biography on the cover of French Leave: “ ‘Wendy Robertson has

written to other novels for teenagers Lizza, and The Real Life Of Studs Mcguire.

Of that novel the review magazine Growing Point has written: ‘The Real Life Of Studs McGuire states fair and square in an urban

dilemma in an up-to-date setting and through strongly contemporary characters…

The action is swift and exciting enough to carry the message to those who read itI

I like

to think that the same may be said of French Leave. Wx

I like

to think that the same may be said of French Leave. Wx

Amazingly

it seems that copies of French Leave is still available through the magic

of the Internet - albeit without its wonderful cover. If you are interested, you

can find it here: https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=1363697073&clickid=RHq3yCxkbxyNUrI3HI1nmWcDUkDR5LzZNRmoWs0&cm_mmc=aff-_-ir-_-66692-_-77416&ref=imprad66692&afn_sr=impact

Afterthought. In combing through my shelves for this new 'Tasting Life

Twice' Project I have come across two versions of the French language edition of

French Leave, so thought I you might like to see the covers.

Perhaps it's also worth noting here in this essay that two of my later novels – Writing at the Maison Bleue and An Englishwoman in France also take place in this France that still sits in my head ... Wx